What Is Google Genie 3? DeepMind's World Model Explained

Hey, Dora is here. A small thing set me off. I was clipping a short reference video for a UX idea, and I caught myself wishing I could “poke” the clip, nudge the scene, change the angle, move the character two steps left, without reopening Figma or touching After Effects. That’s when I circled back to Google’s Genie line. I’d seen the early Genie demos months ago, then the newer “Genie 3” chatter.

I spent a few evenings in late January 2026 reading the official posts, watching the research videos, and comparing them with earlier interactive-environment models I’ve actually tried. Where I could, I recreated small flows from the older public Genie materials. Where access was closed, I took notes and paused when the claims felt fuzzy. Here’s what stuck, with a focus on what “world models” mean in practice, not in press lines.

What Google Genie 3 does

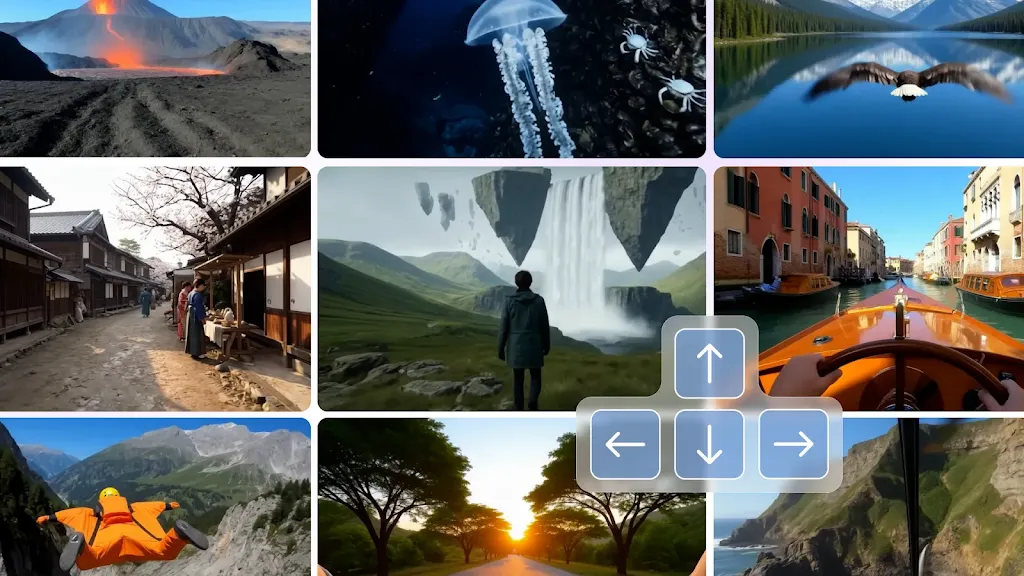

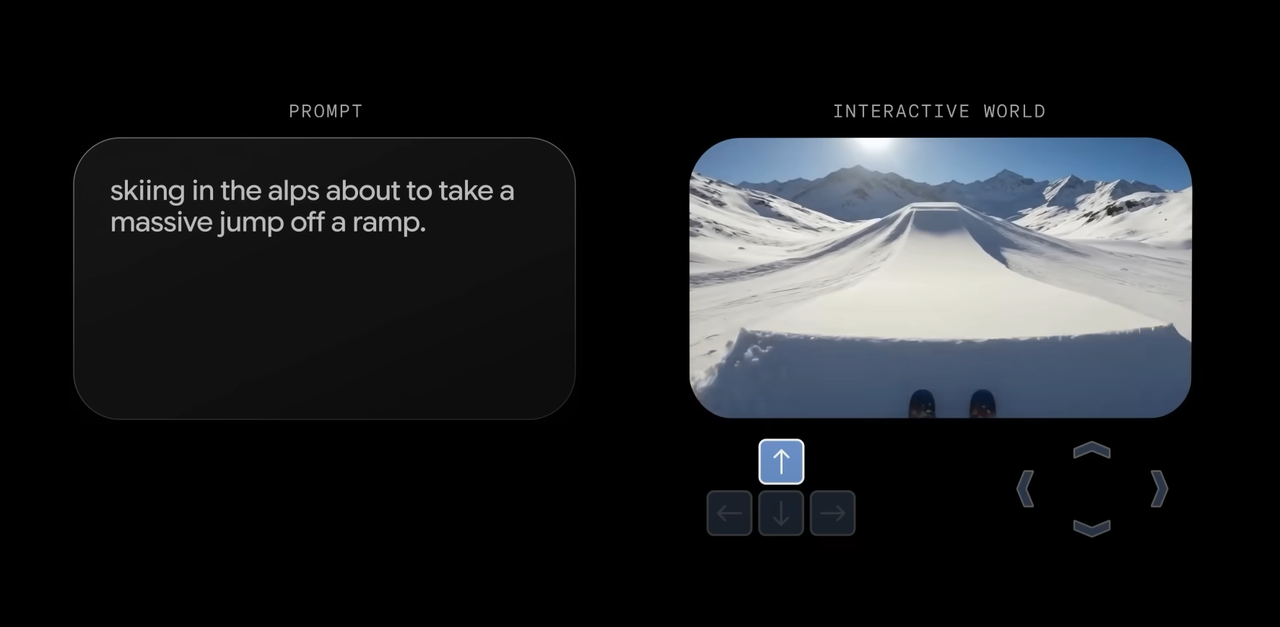

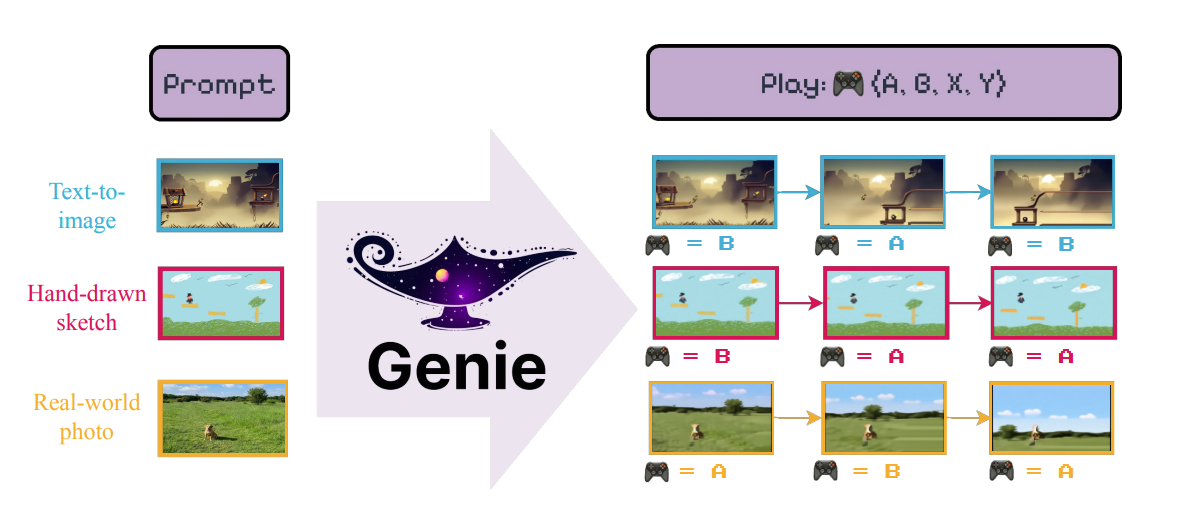

At a high level, Genie 3 is presented as a world model that can turn text or images into interactive, playable scenes, think short 2D or stylized 3D snippets you can actually control rather than just watch. In Google/DeepMind’s demos, you sketch or describe a scene, and the model spins up a consistent environment with objects, physics-ish rules, and a controllable actor. The end result looks like video, but it behaves like a tiny game.

At a high level, Genie 3 is presented as a world model that can turn text or images into interactive, playable scenes, think short 2D or stylized 3D snippets you can actually control rather than just watch. In Google/DeepMind’s demos, you sketch or describe a scene, and the model spins up a consistent environment with objects, physics-ish rules, and a controllable actor. The end result looks like video, but it behaves like a tiny game.

The pitch is subtle but important: instead of rendering one-off frames that only look right from a distance, a world model tries to learn the dynamics underneath. When you press left, the character moves in a way that still fits the world it just imagined. When a ball drops, gravity behaves the same each time. That consistency is the difference between a cool clip and a tool you can use.

What I noticed while comparing Genie 3’s demos to earlier Genie iterations is the push toward longer, more coherent rollouts. Earlier Genies could produce fun, single-level toys: Genie 3 appears to hold rules longer, so actions chain together without the scene unraveling. I say “appears” because I don’t have hands-on with the exact research build. But the clips show fewer weird glitches, fewer moments where a character clips through a wall or where textures melt when the camera pans. The upgrade seems less about flash and more about stability.

In practice, here’s how I’d use something like this if it were in my toolbox today:

- Rough-in a prototype: Turn a sketched layout into a playable mock so stakeholders can feel timing and affordances, not just see them.

- Explore motion ideas: Generate variants of transitions or interactions and pick the one that feels right in the hand.

- Teach or test: Build small, constrained worlds to check a sequence of actions, like onboarding flows or training tasks.

That’s the appeal. Not magic, just less friction in the early passes.

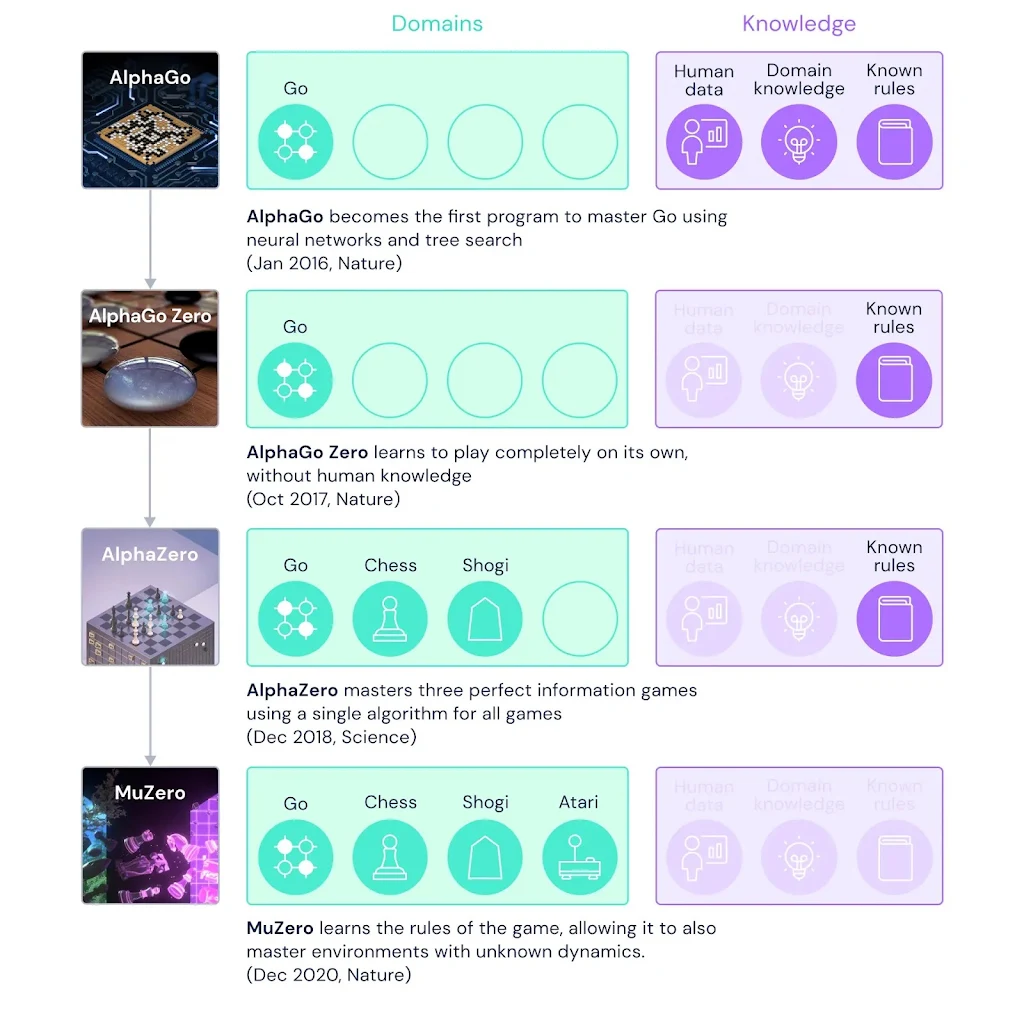

How world models work

I’m not going to pile on jargon. The core idea: a world model tries to learn how a scene changes over time, not just how it looks. If you’ve seen work like MuZero or Dreamer, the thread will feel familiar, learn a compact representation of state, predict how it evolves with actions, and sample visuals that stay in character.

A few practical bits I keep in mind when I hear “world model”:

A few practical bits I keep in mind when I hear “world model”:

- There’s an internal memory of the scene. The model isn’t redrawing from scratch each frame: it keeps track of entities and rules so motion has continuity.

- Actions matter. Instead of only predicting the next frame, it predicts the next state given an action (jump, turn, collide). That’s what makes it playable.

- Coherence costs compute. Longer, stable rollouts mean more careful training and inference. If something feels slow, that’s often why.

World model vs video generator

Most video generators today make plausible pixels, then hope your brain fills the gaps. They excel at short, cinematic bursts and quick edits. But try to control them and the illusion slips. The moment you add input, the model has to remember what exists, where it is, and how it behaves.

A world model flips the priority: remember first, render second. It costs more up front, data, training, guardrails, but it pays off in interactivity. In my notes, I wrote: “Video gen is a storyteller: world model is a stage manager.” Not a perfect analogy, but it explains why Genie 3 feels different. You’re not only asking, “Can you make this look like a platformer?” You’re asking, “Can I play it twice and get the same rules?” That’s the bar that matters for work.

Key capabilities demonstrated

Since I didn’t have direct access to the Genie 3 build, I anchored on what’s visible and consistent across official demos and papers, and on what I could reproduce with older public artifacts. Here are the parts that felt meaningful:

Since I didn’t have direct access to the Genie 3 build, I anchored on what’s visible and consistent across official demos and papers, and on what I could reproduce with older public artifacts. Here are the parts that felt meaningful:

- Prompt-to-playable scenes: Turning text or sketches into small environments you can control. In older Genie materials, I could go from a rough sprite sheet to a simple platformer in minutes. In Genie 3 demos, the same idea shows up with better stability and longer sequences. The jump arcs look repeatable. Collisions look less mushy.

- Rule persistence over time: This is the quiet win. In video gen, longer clips often drift, objects morph, lighting stutters, layouts crawl. In Genie-like world models, the “physics” and object identities stick around. I saw fewer continuity breaks in the Genie 3 clips compared with earlier ones.

- Editable starting states: Some demos show seeding the world from an image or layout, then playing from there. That matters more than it sounds. It means I can rough-in in my tool of choice, then push into a playable test without rebuilding assets.

- Action-conditional rollouts: The model responds to inputs with consistent outcomes. Press left: you move left. Press up near a ledge: you grab it. This sounds basic, but it’s the difference between a toy and a testbed.

- Stylized but legible visuals: The look sits somewhere between retro game art and painterly video. It’s not photoreal, which is a feature for many workflows. You get clarity without uncanny edges.

- Longer horizons, still bounded: I noticed rollouts that feel like dozens of seconds with stable rules. But they’re not open-world sandboxes. The spaces are compact on purpose, which, frankly, is fine for most prototyping.

Where it rubbed a bit:

- Latency and iteration speed: In earlier experiments, I often waited longer than I wanted for a new “world” to stabilize. If Genie 3 is heavier, I expect similar waits. That’s okay if the outputs are reusable, less okay if you’re exploring.

- Control over constraints: Designers want dials: gravity strength, friction, collision tolerance. The demos rarely show explicit knobs. If control exists, it’s probably tucked into prompts or hidden parameters. I’d like visible sliders.

- Asset handoff: Even when a scene feels right, exporting it into a production pipeline is nontrivial. Sprite extraction, hitboxes, state machines, these are glue tasks. I didn’t see clear pathways in public materials yet.

One small joy from my side tests with earlier Genie artifacts: the mental load dropped. I wasn’t hunting for the “right” plug-in to fake physics in a mock. I typed, generated, and pushed a character around. It didn’t make me faster at first, but it made me less tense. That mattered more than I expected.

Current access status

As of early February 2026, Genie 3 sits in research land. There are papers, talks, and demo videos. I haven’t seen a broad, public API you can sign into with a Google account, and I don’t have a consumer release in any Workspace tool. If you’re reading this later and that changed, great, drop me a note and I’ll update.

Where to look right now:

- Official research posts from Google DeepMind. Start with the original Genie paper and blog for grounding, then skim follow-up talks that mention “Genie 2” or “Genie 3” as internal iterations.

- Conference recordings and lab demos. They often show the newest rollouts months before any public preview.

- Academic preprints referencing “world-model video generation” or “interactive environment generation.” The naming varies, but the mechanics rhyme.

Practical takeaways if you’re deciding whether to wait, build, or ignore

- If you prototype interactions a lot (product, game, learning), keep an eye on Genie. Even a limited public preview would be useful for previsualization and testing feel.

- If you need production assets today, don’t plan around it. Treat it as a sketching companion, not a pipeline.

- If you care about research replication, you can still learn a lot by playing with open world-model projects like Dreamer variants and by reading Genie’s method sections. The principles transfer.

I’ll add one small, slightly boring note. The search term “Genie 3 Google” pulls in a mix of older Genie posts and newer world-model news. Some write-ups blur marketing and research. When in doubt, trace claims back to the DeepMind blog or the paper PDFs. It saves time and keeps expectations steady.