DeepSeek V4 1M Token Context: How to Prompt Entire Codebases

Hey my friends. I’m Dora. The first time I dropped a full project into DeepSeek V4’s 1M-token window, I didn’t feel powerful. I felt cautious. A million tokens sounds like bottomless coffee, but anyone who’s tried to think for hours on a caffeine drip knows the edge blurs. I wanted to see if this new context size would actually change how I work, or just encourage me to paste more.

I spent a few days (Jan 27–30, 2026) using DeepSeek V4 1M tokens on three tasks I run into often:

- reading a medium-sized monorepo without setting up locally,

- tracing a bug across services that talk too much,

- and asking for refactor suggestions that don’t wreck the tests.

What I learned: you can fit a lot, but the model still needs you to point on the map. The gains didn’t come from stuffing in more files: they came from how I staged the prompt and how I asked the model to move through it.

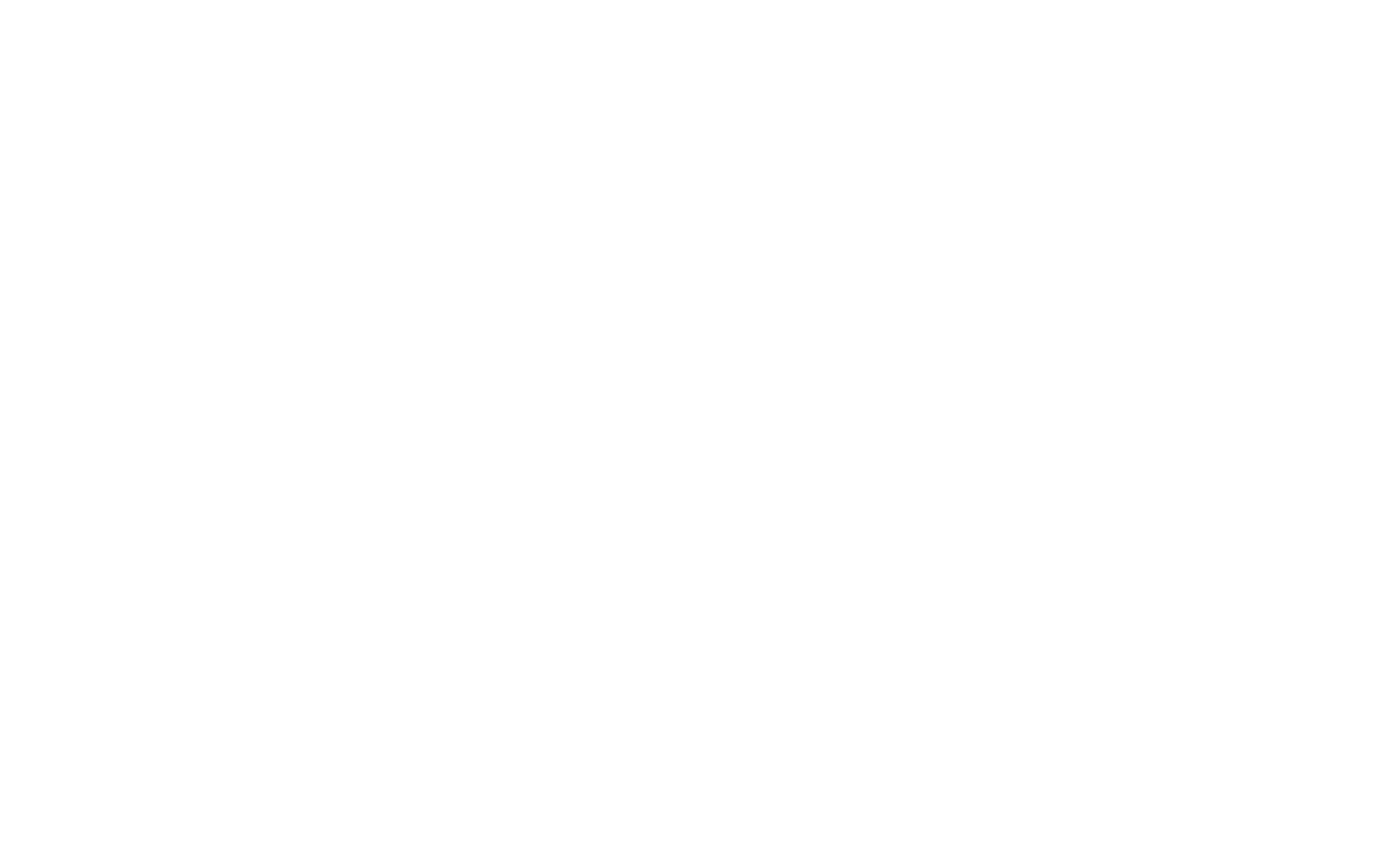

What 1M Tokens Actually Means

I don’t care about the number by itself. I care about what it holds with a clear head.

I don’t care about the number by itself. I care about what it holds with a clear head.

A token isn’t a word. It’s a chunk, sometimes a full word, sometimes part of one, sometimes punctuation. In English text, I usually treat 1 token as ~0.75 words for rough planning. For code, tokens come fast: braces, dots, method names, all sliced up. A million tokens is a lot of territory, but it’s not infinite attention.

What changed for me this week: I stopped pruning as aggressively. With 128K contexts, I would summarize aggressively and keep only the hot path. With 1M, I could keep the hot path plus the “cold” files that tend to surprise me later (config, migrations, build scripts, workflow glue). That said, if I dumped everything at once, answers got vague. When I fed the model in stages, with clear signposts, the outputs felt grounded.

Lines of Code Equivalent

Rough math I used while working:

- Many repos mix code and docs. In code-heavy folders, I saw ~2–3 tokens per character in dense languages, but a practical shortcut: think ~4 tokens per line for simple lines, ~8–12 for real-world lines with indentation, names, and comments.

- At that pace, 1M tokens holds somewhere around 80K–150K lines of code, depending on style and language. A TypeScript service with comments and lint-friendly naming sits on the higher side. Minified bundles explode the count and aren’t worth including.

In practice, my “safe fit” was ~60K lines of meaningful source + targeted docs and tests. I could go higher, but latency climbed and answers softened. Your mileage will vary with tokenizer rules and language mix.

vs Current Models (128K)

Jumping from 128K to 1M feels less like a bigger backpack and more like bringing a rolling cart. You can carry more, but you won’t sprint.

What I noticed:

- Latency: Whole-context prompts took noticeably longer. When I chunked the session (stage-by-stage), latency felt manageable.

- Recall: With 128K, the model often “forgot” earlier files unless I repeated the key part. With 1M, it didn’t forget, but it sometimes generalized instead of quoting specifics. I had better luck when I asked it to cite file paths and line ranges where possible.

- Precision: The bigger the context, the more you need indexing behaviors in your prompt. Otherwise, you get competent summaries that dodge the messy edge cases you actually care about.

If you’re hoping 1M tokens means “no more prompt engineering,” I wouldn’t count on it. It shifts the kind of steering you do.

Prompt Structure for Large Codebases

I stopped thinking of the prompt as a message and started treating it like a reading plan. The model can read a lot now, but it still benefits from a table of contents and a trail.

I stopped thinking of the prompt as a message and started treating it like a reading plan. The model can read a lot now, but it still benefits from a table of contents and a trail.

What worked best for me looked like this: short system framing, concise project index, a declared order of exploration, then a specific task. And then I kept the conversation going in rounds, not one mega-prompt.

File Ordering

I got more reliable answers when I told the model what to open first, second, third. A single list at the top helped it build a mental stack:

- Start with the entry points (CLI, HTTP handlers, jobs). It anchors the flow.

- Then the composition layer (DI container, main.ts, app.py) where dependencies wire up.

- Next, the core domain modules and their interfaces.

- Only then: helpers, utils, and cross-cutting pieces (logging, telemetry, config).

- Tests last, unless I’m debugging a specific failure, in that case, start with the failing spec to set expectations.

I also included “do not read” notes for folders that look important but aren’t: generated code, compiled assets, snapshots. It saved tokens and kept the model’s attention on living code.

A small trick: I asked the model to maintain a rolling list of “active files” (paths and short summaries) and to update it as we moved. When it drifted, I could point back to that list and say, “Stay inside this set for now.” That kept the answers concrete.

Dependency Mapping

One of the most useful passes was asking for a dependency map early, not as a diagram but as a simple table of edges: module A imports B, B uses C, C hits env variables, and so on. I kept it textual and terse.

What this did in practice:

- It exposed stray dependencies (the kind that bleed concerns across folders).

- It gave me a shortlist of “pressure points” to review before any refactor.

- It helped the model reference the right place when I asked for changes.

I also made the model state assumptions, what it inferred from naming, comments, or tests. When an assumption was off, I corrected it once, and the later steps stayed cleaner.

One warning: asking for a full dependency map on a large repo in a single shot led to timeouts and vague graphs. I had better results scoping it by layer (e.g., only data-access, only HTTP handlers) and then merging the notes myself. It took an extra 10 minutes but paid back in accuracy.

Chunking Strategies When Needed

Even with a 1M-token window, I still chunked. Not because it couldn’t fit, but because my thinking was better in stages, and the model answered more precisely when I narrowed its field of view.

Even with a 1M-token window, I still chunked. Not because it couldn’t fit, but because my thinking was better in stages, and the model answered more precisely when I narrowed its field of view.

A few patterns that held up this week:

- Stage the brief: I started with a small context, project index, task, known constraints, then asked for a plan of reading and verification. Only after that did I feed the code in the order we agreed on.

- Limit the active set: For a refactor, I kept just the 5–12 files in play and asked for changes with explicit paths. If an edit touched a shared util, I added that file in the next turn. The model stayed tighter.

- Summarize at edges: Before moving to a new folder, I asked for a short summary of what we learned and any uncertainties. These summaries acted like breadcrumbs across turns without re-pasting every file.

- Use retrieval on purpose: For repos that didn’t fit comfortably, I used embeddings to call in files by query (“payment id normalization”, “retry backoff”). I kept the retrieved set small per turn, usually under 40K tokens, so replies didn’t blur.

- Verify forward, not backward: Instead of asking, “Did you use everything I pasted?” I asked, “Point to the specific functions and lines your suggestion depends on.” That forced concrete references and made errors obvious.

Friction I hit:

- Latency creeps when you send full-context messages every turn. Staging cut my average response time from 70–90s to 20–40s on the same tasks.

- Cost matters. Large prompts add up. I saved tokens by trimming comments that restated the obvious, removing compiled artifacts, and skipping vendor bundles.

- Position effects are real. Content at the very start or end of a giant prompt tends to be more “available.” I countered this by repeating the tiny, critical constraints near the end of each turn.

Who benefits from the 1M window?

- If you live in monorepos, handle audits, or do cross-cutting refactors, it buys you fewer setup steps and less local indexing overhead. It’s a calmer starting point.

- If your work is mostly focused bug fixes in small services, the extra capacity won’t help much. A smaller context plus a tight retrieval pipeline will feel faster.

A note on trust: I asked the model to cite exact code lines for risky changes (migrations, auth). When it hesitated or paraphrased, I treated that as a flag to narrow the scope or paste the specific file again. That small habit prevented a couple of near-misses.

If you want the formal description of model limits or tokenizer behavior, check the provider’s docs. When I needed specifics, I went back to the official model card and context-window notes. It kept me honest about what I was asking the model to do.

This isn’t magic. It’s just a bigger table. Useful, if you arrange the chairs.

I keep thinking about one small thing from Tuesday: I asked for a fix, and the model suggested changing a function that looked right at a glance. It wasn’t. The bug lived in a helper two layers down. A million tokens didn’t change that. My notes did.