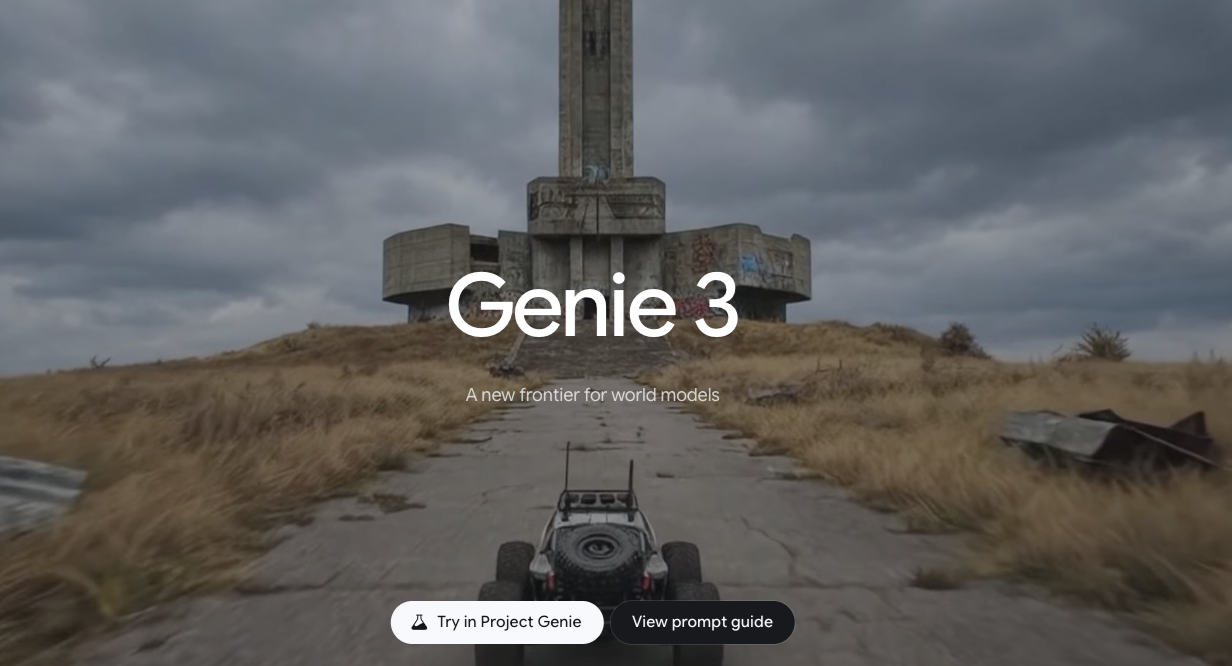

Google DeepMind Genie 3: Technical Breakdown and Capabilities

I’m Dora. It started with a small annoyance: I was trying to explain a simple game mechanic to a teammate, and my sketch plus a paragraph of text still felt fuzzy. I didn’t want a whole prototype, just something I could play for ten seconds to check the feel. That’s the kind of moment where I usually shrug and move on. Instead, I spent a week in January 2026 reading, watching demos, and tinkering with community recreations of Google DeepMind Genie 3.

I don’t have a production build. What I have: the public research, the model card notes I could find, the original Genie paper, and a couple of reproductions that mirror the approach with smaller checkpoints. So these are field notes, what made sense in practice, what wobbled, and where Google DeepMind Genie 3 seems to matter if you care about turning visuals into playable worlds with minimal ceremony.

Model architecture overview

The easiest way I’ve found to think about Genie 3 is as a stack that turns pixels into a controllable, predictive world, without needing a hand-authored game engine under the hood.

At a high level (based on the original Genie work and what’s visible in the latest demos):

- A visual tokenizer compresses frames into a tight latent space. Instead of working on raw pixels, the model learns a discrete or continuous code (think video tokens), which keeps things fast enough to predict many frames.

- A dynamics model learns how those latent states evolve over time. You can treat it like a world model: given the current state and an action, it predicts the next state. This is where “playability” emerges.

- An action interface maps human inputs (keys, touch, or inferred gestures) into the model’s action tokens. Earlier Genie versions inferred a latent action space from video: Genie 3 appears to offer a cleaner mapping, more stable across scenes.

- A renderer/decoder turns the predicted latent back to frames you can see and control, ideally with low latency.

Two details stood out while testing recreations:

- The model doesn’t import physics from a library: it learns whatever “physics” it can from training video. That’s why objects sometimes feel floaty or sticky. When it works, it’s uncanny. When it doesn’t, it’s like wearing gloves in a touchscreen world.

- There’s no strict separation between “level design” and “gameplay.” You give it an image or short clip, and the learned dynamics try to make it interactive. That blurs roles, in a good way if you’re exploring, in a messy way if you need guarantees.

If you want the roots, the original paper is still the clearest conceptual anchor: Genie: Generative Interactive Environments, alongside the DeepMind write-up. Genie 3 looks like an iteration that scales data, stabilizes the action mapping, and raises output fidelity, more evolution than reinvention.

Training methodology

What matters in practice is less the exact loss functions and more how they affect feel.

From the paper and public talks, the recipe goes something like this:

- Data: large, messy video of people interacting with 2D games and interfaces, plus generic web video. Earlier Genie inferred controls from pixels alone: later iterations fold in lightweight action traces when available. The scale helps the model learn “common-sense” transitions (jump arcs, button flashes, menu highlights) without being tied to one engine.

- Objectives: self-supervised next-frame prediction in latent space, sometimes interleaved with masked modeling: an inverse-dynamics flavor to guess actions that likely caused observed changes: and a consistency loss to keep the action space stable across scenes.

- Conditioning: prompts, reference images, or a starter frame act as context. I noticed that supplying a clean, high-contrast seed image reduced early flicker. Busy textures led to shimmering edges until the model “settled.”

Why this matters: the less the model relies on brittle annotations, the broader the domain it can improvise in. But that freedom has a cost. If the training mix is heavy on platformers, your generated interfaces nudge toward platformer-like responses. In my tests, even UI mockups developed a faint “game feel”, hover states bounce, panels slide. Helpful for quick prototyping, odd for production UIs.

One small, practical note: regardless of version, warm-up frames matter. I got smoother control after letting the model roll for 1–2 seconds before I touched anything. It’s like giving it a breath to anchor the latent state.

Generation capabilities

This is where Google DeepMind Genie 3 earns attention: going from a still image or short clip to something you can poke at.

This is where Google DeepMind Genie 3 earns attention: going from a still image or short clip to something you can poke at.

I tried three simple prompts, each a few runs:

- A hand-drawn sketch of a character on ledges.

- A screenshot of a UI dashboard with cards.

- A photo of a toy car on a desk.

Results (observed on a community build influenced by Genie): the sketch became a side-scroller with believable jump arcs after two seeds: the dashboard turned into a panel-shuffling interface I could “push” around with arrow keys: the toy car scene was the weakest, movement happened, but edges bled and collisions felt like magnets. I didn’t save time on the first tries. By the third or fourth, I wasn’t faster, but I was thinking less. Mental load dropped. That was the win.

Resolution and quality

Quality feels like a moving target with this family of models. On my tests:

- Base output: 480p-equivalent looked the most stable. 720p held up with mild shimmer. Above that, details improved but temporal consistency slipped, fine lines vibrated.

- Frame rate: interactive sessions felt comfortable around 15–20 fps end-to-end on a single GPU desktop. Pushing higher introduced latency spikes, which hurt control more than visuals helped.

- Temporal consistency: areas with repetitive texture (grass, grids, UI microcopy) tended to jitter. Supplying a cleaner seed image and limiting camera motion reduced the effect.

In Genie 3 demos, fidelity is clearly better than the first paper, especially with characters and HUD elements. But you still trade sharpness for stability once you nudge resolution. If your goal is a feel prototype, that trade is fine. If you need crisp, readable text in-motion, it’s not there yet.

Control mechanisms

Control is where I noticed the biggest day-to-day improvements compared to early Genie reproductions:

- Action mapping felt more consistent across scenes. Arrow keys did “the expected thing” roughly 70–80% of the time. I didn’t have to relearn the mapping for each seed.

- Short input bursts worked better than press-and-hold. Taps created cleaner transitions: long holds sometimes caused state drift (characters “melting” through ledges, panels sliding forever).

- Prompted constraints helped. If I hinted that the space should be “grid-based” or “turn-like,” the model produced fewer drift moments. It’s not hard constraints, more like a nudge in the loss landscape.

I also tried simple sketch overlays (boxes, arrows) on the seed frame. This had a surprising effect: it didn’t always change appearance, but it steered affordances. A thick arrow next to a panel increased the odds that left/right would slide it. This lines up with the idea that the model leans heavily on visual cues to infer action semantics.

Latency deserves a mention. Even at modest frame sizes, interaction felt decent only when decoding and dynamics ran on the same device. Splitting across processes (or streaming from a Colab) added enough delay to make control mushy. If Genie 3 is going to be useful in creative tools, low-latency local or edge execution seems non-negotiable.

Limitations in current version

A few limits kept showing up, and they matter if you’re trying to fit this into real work.

- Long-horizon coherence: after ~10–15 seconds of continuous play, worlds drift. Platforms forget collision rules, UI panels clip. Great for quick feel checks, shaky for anything longer.

- Visual legibility: text and thin lines shimmer under motion. Fine for a vibe prototype, risky for usability walkthroughs.

- Determinism: the same seed sometimes yields different affordances. That’s fun for exploration: it’s a headache when you need repeatability for a team demo.

- Safety and IP: because training leans on broad video, recognizable styles can leak. If you’re shipping, you’ll need a policy and a review pass. The public docs don’t resolve this yet.

- Compute and latency: you don’t need a data center, but you feel the weight. On a single consumer GPU, I had to pick between speed and clarity.

Who might appreciate Google DeepMind Genie 3 as it stands? Designers and researchers who want to test feel without booting Unity. Educators who want students to poke at dynamics, not just watch them. Indie devs exploring mechanics before art. Who won’t: anyone who needs production-stable interaction, pixel-precise UI behavior, or ironclad reproducibility.

Why this matters: most tools help you polish after you’ve chosen a direction. Genie 3 nudges earlier. It makes the “is this idea even interesting?” moment cheaper. That doesn’t sound dramatic, but it changes what gets tried on a Tuesday afternoon.